Well, here we are: the last full weekend of summer, and the last installment of my Prince (Protégé) Summer guest series. We’re covering a lot of ground this time, because for the last two decades of his life, Prince took a notably more laid-back approach to his spinoff acts. In part, this was because he just wasn’t a big enough star anymore to sustain multiple artists’ careers in addition to his own. I think, however, that the shift was philosophical as well as pragmatic: with one notable exception, Prince’s latter-day side projects were more conventional mentor/mentee relationships, rather than the svengali-like practices of his earlier “Jamie Starr” days. In some ways, that made these projects less memorable than, say, the Time or Vanity 6: those thinly-veiled Prince albums recorded when he was at the peak of his powers as a songwriter and producer. But it was also a more sustainable and, I think, humane approach to cultivating talent; one much better suited to Prince’s latter-day reputation as a fierce protector of artists’ rights.

The years immediately following the release of 1-800-NEW-FUNK were fallow ones for the artist then known as the Artist Formerly Known as Prince. As I mentioned last time, most of the side projects sampled by the compilation were quietly cancelled; only Mayte’s Child of the Sun was released in 1995, and then only in Europe. O(+>’s own career was up and down in the latter half of the ’90s: up with Emancipation in 1996, mostly down after that. And, while NPG Records‘ attempts to sell music via Internet mail-order were groundbreaking for the time, they were also mismanaged and inefficient; just ask anyone who preordered Crystal Ball from O(+>’s website in 1997. By the end of the decade, the once-prolific idolmaker was the one seeking other artists’ support: 1999’s Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic, a bald-faced attempt by O(+> and Arista to replicate the success of Santana‘s Supernatural, awkwardly paired the Purple One as a reluctant “legacy artist” alongside then-current names like Eve, Gwen Stefani, Ani DiFranco, and Sheryl Crow.

After the turn of the century, however, the pendulum began to swing the other way. The publicity push around Prince’s 2004 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, culminating in the release of his comeback album Musicology and its massive accompanying tour, restored him to household name status. It was also around this time when he began to more prominently position himself as a mentor to young artists, particularly women, performing with Beyoncé and Alicia Keys at various award shows and afterparties. Soon, in advance of his 2006 album 3121, he took a relative unknown under his wing: a former member of Girl’s Tyme (the group that eventually became Destiny’s Child) named Támar Davis.

I’ll be honest: I’m not a huge fan of Támar’s brand of contemporary R&B (this will be a recurring theme for this post, by the way). I totally understand and respect her talent; the girl can sing and she has stage presence, both of which are amply demonstrated by the above footage of her February 2006 show with Prince. But her featured track on 3121, “Beautiful Loved & Blessed,” is just sort of a snoozefest to me; before writing this blog, I can’t remember the last time I listened to it all the way through. Most distressingly from my perspective, there’s very little of Prince’s personality to be heard in his collaborations with Támar: it’s workmanlike, radio-friendly early 21st century R&B that just happens to be co-written and performed by Prince. That’s fine, of course, but it’s not my cup of tea.

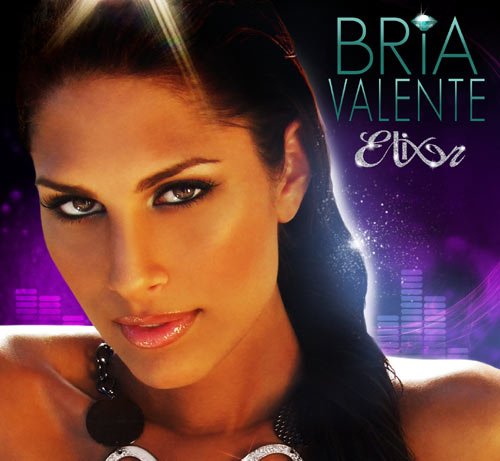

Támar was supposed to release a Prince-produced debut album in 2006; but, like so many of his other latter-day side projects, it was delayed and ultimatey cancelled. She soon drifted from Prince’s orbit. Around the same time, Prince became involved–professionally and romantically–with an aspiring singer from Minneapolis named Brenda Fuentes, who he rechristened as Bria Valente. As the renaming suggests, theirs was a more conventional Prince protégée relationship; Valente, it’s worth noting, also shares a certain statuesque, ethnically ambiguous look with previous “Prince girls” like Vanity and Mayte. One thing I will say about her album with Prince, 2009’s Elixer: it does feel more identifiably “Prince”-like than “Beautiful Loved & Blessed.” The problem is that it’s also probably the most boring thing Prince ever did. Not bad, necessarily–it’s much too dull to be bad. But as far as Prince’s “girlfriend albums” go, I’ll take the spectacularly awful (yes, even Carmen) over the utterly inconsequential. Listen to “Here Eye Come” if you want, but don’t feel too bad if you don’t; Prince actually packaged Elixer with two of his own albums, and I still don’t know anyone who’s bothered sitting through it.

After Prince’s brief relapse to his old svengali ways with Valente, it would be easy to brush off his next major collaborator, Cameroonian singer-songwriter Andy Allo; I certainly did at first. In fact, I nursed a bit of a grudge against Allo for a while, because the first time I encountered her was on Prince’s dreadful 2011 rejiggering of one of my favorite outtakes, “Extraloveable.” Like Támar, she still isn’t my cup of tea: her 2012 album Superconductor just sounds like a bunch of middling jams by that era of the New Power Generation, and the Internet-only acoustic mini-album she did with Prince, Stare, sounds like a compilation of those horrible YouTube covers by white girls with guitars. I’m willing to accept, though, that it’s not about Andy; it’s just a matter of taste. And I can appreciate the fact that by his last half-decade on the planet, Prince had shifted from producing boutique albums as (ahem) vanity projects for his paramours, to genuinely fostering young talent (as long as that young talent came in the form of a statuesque, ethnically-ambiguous woman…but hey, nobody’s perfect).

After Prince’s brief relapse to his old svengali ways with Valente, it would be easy to brush off his next major collaborator, Cameroonian singer-songwriter Andy Allo; I certainly did at first. In fact, I nursed a bit of a grudge against Allo for a while, because the first time I encountered her was on Prince’s dreadful 2011 rejiggering of one of my favorite outtakes, “Extraloveable.” Like Támar, she still isn’t my cup of tea: her 2012 album Superconductor just sounds like a bunch of middling jams by that era of the New Power Generation, and the Internet-only acoustic mini-album she did with Prince, Stare, sounds like a compilation of those horrible YouTube covers by white girls with guitars. I’m willing to accept, though, that it’s not about Andy; it’s just a matter of taste. And I can appreciate the fact that by his last half-decade on the planet, Prince had shifted from producing boutique albums as (ahem) vanity projects for his paramours, to genuinely fostering young talent (as long as that young talent came in the form of a statuesque, ethnically-ambiguous woman…but hey, nobody’s perfect).

Perhaps most emblematic of this shift was one of Prince’s last protégées, Judith Hill. While certainly beautiful (and ethnically ambiguous–she’s of Japanese and African descent), Hill was already establishing herself in the music industry when Prince took her under his wing; he first “discovered” her not long after her appearance in the Academy Award-winning 2013 documentary 20 Feet from Stardom. One gets the sense that Prince approached their joint project, 2015’s Back in Time, as a collaboration between equals: his influence is certainly all over the record, but so are those of artists Hill and Prince mutually admire, such as Stevie Wonder and Chaka Khan. Hill is a “protégée” in the sense that she benefited from Prince’s tutelage, but she’s also allowed to stand on our own feet as an artist.

And this, to be honest, is one of the many things about Prince’s passing that make me sad. For too long, the history of Prince and his associated artists was one of control and mutual resentment: he had a well-known tendency in his youth to micro-manage his protégés, and few of their working relationships with him ended on good terms. By the end of his life, however, Prince seemed to have found a way to pass on his expertise without bending others to his will. I may not be a hardcore fan of Támar or Andy Allo (or, if I’m honest, Judith Hill), but I would have loved to see what this new, more generous Prince might have done with some of the younger artists I do like; when I heard he’d been hanging out with Kendrick Lamar last year, for example, I was downright gleeful.

Unfortunately, we’ll of never know what Prince might have accomplished with Kendrick, or anyone else for that matter: his passing in April cut short what was shaping up to be a truly fascinating late-career creative rebirth, to say nothing of a remarkable life. But I do take some comfort in observing that by the end, the notoriously spotlight-jealous artist seemed to have finally learned to take a step back and allow others to shine. The Prince of 2016 was a long way from the 23-year-old pelting Jesse Johnson with Doritos backstage on the Controversy tour; and, while I’ll admittedly take the Time over his more recent projects any day, I think that transformation was a good thing. It was a long, strange trip for Mr. Jamie Starr. I’m glad that in this area, at least, he was able to find some resolution.

So there you have it; that’s the last I’ll be writing about Prince protégés for a while. My next guest post will, I think, be Prince-related, and then I’ll probably take a break and write about some other things. If you’re just starved to see more of what I have to say about Prince, though, remember to check out my song-by-song chronological blog dance / music / sex / romance. And of course, you can always see what I have to say about a whole lot of other stuff on Dystopian Dance Party. Thanks for reading. Happy Prince Summer!

SUPERB article Zach! I didn’t know Tamar Davis was in the embryonic ground for Destiny’s Child. That was excellent information. It was good you pointed out how Prince’s relationships with his protegees changed as he matured. His “girlfriend albums” were always a mixed bag of course. For every Vanity 6 and Jill Jones,there was a Carmen Electra. But the information here on the final two decades of Prince protegees is strong and detailed.

Whatever u say about Prince just be careful about calling him jealous or anything else, cause I don’t believe u worked with him on a personal basis your just speculating, so unless u really know him and actually seen him doing all the things your writing about, u better be respectful of him, or u will make a lot of enemies and no one will ever want to read or buy anything your putting out there! God have mercy on your soul!

Thanks for this! Do you know who is the current producer or what is the record label for Judith Hill?